My father’s brain was connected by wires. His mind worked through the process of circuitry funneled through electricity and programming in ways that paved the way for modern technology. In the corner of a basement, radio equipment jolted voltage ideas from boxes of switches and switchboards. Out of that came a profession that gave me a modest childhood. For 42 years, my father ran a professional marathon, fixing machines and fueling innovation for the automobile industry that also served as a catalyst for airplane engines. For 42 years, my father was an electrician for General Motors. His second home was Allison Gas Turbine, and there he kept the machines not just running smoothly but simply running. . . period.

What all of this did was make us a Chevy household. There was not a time when it was not. Not that he came home with the latest and greatest luxury vehicle or fancy sports car. Our Midwestern middle-class lifestyle saw family comfort like the C10 turned S10 turned Silverado. We traveled the country in a Chevy that carried a truck camper shell on its back throughout the 1970s and 1980s. This transcended into the boat that was a Caprice Classic in which I shoved as many friends as I could for a night cruise. By the 1990s, I spent many nights at the university making out in the back seat of a 1996 Corsica or getting lost down city streets listening to 1960s jazz and smoking Gauloises.

“You better watch what you say about my car. She’s real sensitive.”

I did not give a shit about cars, what they were, what they resembled. Hell, it was not until I read Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance that I finally understood the symbolism. I did not care what -cid (cubic inch diameter) the engine block weighed, the chassis did not impress me, nor whether it was a V8 350-HP or a 320 super sport. Can it simply get me to where I wanted to go?

I grew up with friends whose waking hours (and probably night dreams) were about one muscle car after another. They bought model kits of cars that haunted their dreams — cars they could not afford even if they could drive. Their notebooks were littered with drawings of a 1969 (or 1972) Corvette Stingray or the 1970 Camaro Z28. The care in the shading, the strokes of each line, these classic works of art went right along with the grease tucked underneath fingernails and modest mullet protruding from the “name your favorite car brand” baseball cap. You can smell them coming down the hall and ZZ Top and Billy Squire rolling out of the speakers of their Monte Carlo.

My artistic skills came in the form of ‘80s metal band names and mythical creatures. I’m not sure how my father felt that I did not share in his passion for the marvels and innovation of the automobile. What he did not realize is that I actually did care even if I did not know how to channel that. But it came to light In the 1970s. I was obsessed with weekly visits to the library. My mom would drop me off to pick out weekly books to absorb. My best friend was a book, and I tried to spend as much time as possible with it.

Zen and the art of vehicle appreciation

One day, I brought home a book that featured concept cars of the future. I wish my memory could pinpoint the name of that book or what it looked like. About an hour of scouring the Internet, nothing of the sort emerged. But I remember sitting on the floor with friends, skimming through the book and picking out what machine would be the most magnificent. Some flew. Some floated. Others were just way out there. Driverless vehicles. Get outta here! My friends and I were completely fascinated at the possibilities the future would hold. Will we ever be cruising around in a flying car painted in Ace Frehley metallic gray?

This book would hold secrets not even Walt Disney’s Tomorrowland was willing to expose to the world. These designs were made of science fiction. It made me realize that I was not simply fascinated with the automobile, but more so the concept of imagination and that’s what the automobile was designed from.

Every so often, I think about that book and how it challenged tradition. Years later, I came across a book my dad owned, “Chevy Classics” [1.] The book starts in the 1920s and moves through time until it stops at the iconic 1974 Vega (Chevy’s answer to the international sports vehicle).

Back to the future of Chevy love

The concept was there and at one time or another, these designs were revolutionary. It was fun going through the pages and see how engineering transcended through the decades. The subtle nods to cultural design. Two favorites stood out.

First up, the 1956 Bel Air. Slicker in design than the 1954 Bel Air, the Chevy icon was nicknamed “The Hot One.” With an optional 205 HP four-barrel V8 or the beefier 225 HP. The car has style and elegance without being pretentious.

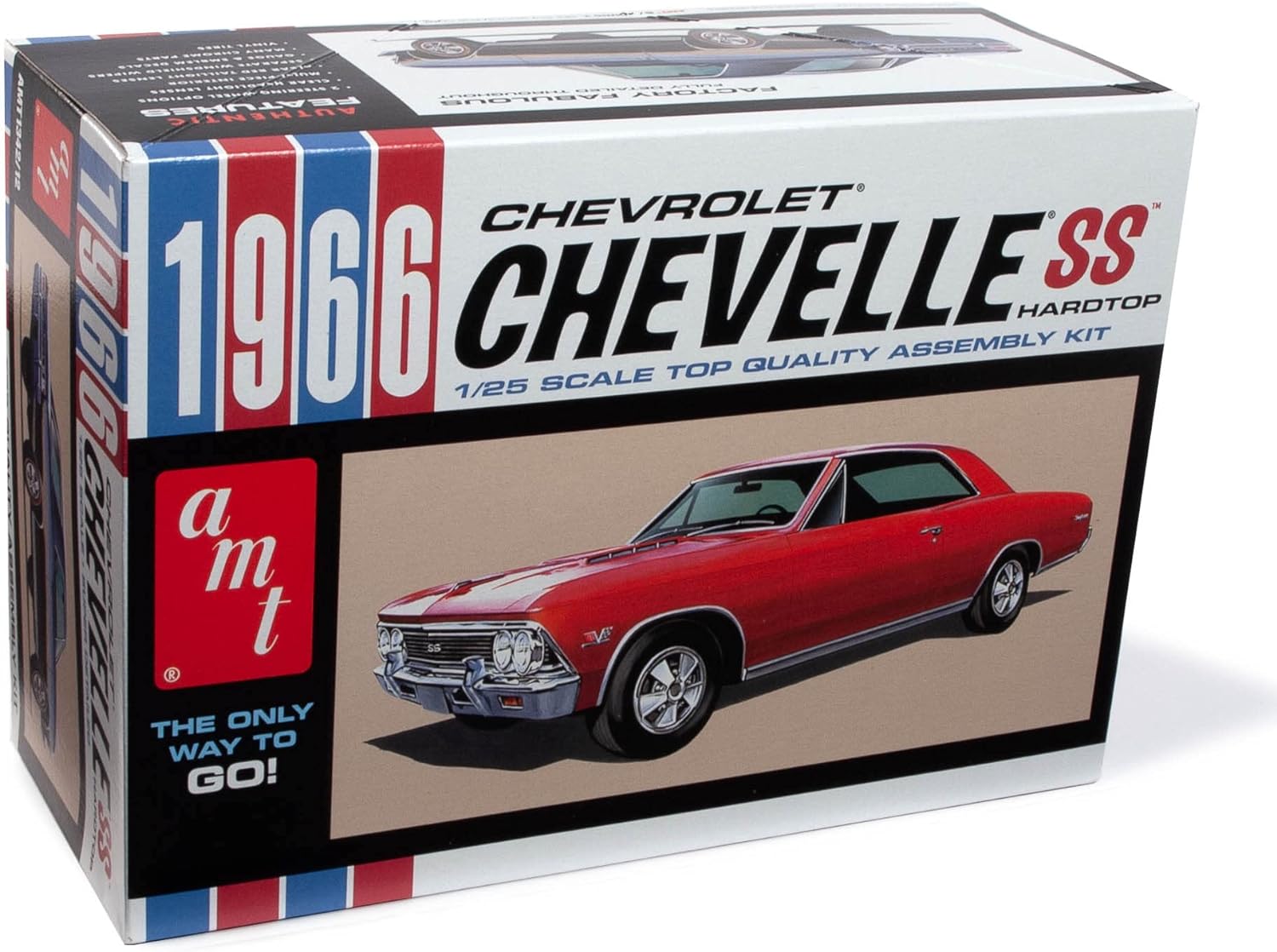

Second car to tug at my heartstrings was the 1966 Chevelle SS 396. This was Chevy’s entry into the muscle car world. The design is mysterious, The body unpredictable to those who controlled it. The car contained the big-block 396 V8 exposed for everyone to notice. You could get a 325 HP but why stop there? 360 and 375 were available. Convertibles were available but hardtops are where it’s at.

Does this now make me a grease head? Probably not, but I can now say I visibly have a deeper appreciation that goes beyond staring at a Davis Divan with perplexity to wondering when flying cars will make an entrance into society. This also may have begun my fascination with retrofuturism, especially in science fiction art. In hindsight, I’m glad flying cars are not a thing. If we cannot nail down autonomous vehicles and assure safety, then how are we to have assurance for flying vehicles. In concept, it’s the same issues automakers dealt with in the 1920s, just at much slower speeds. One day. . . one day, the concept will become the reality.

No Comment! Be the first one.