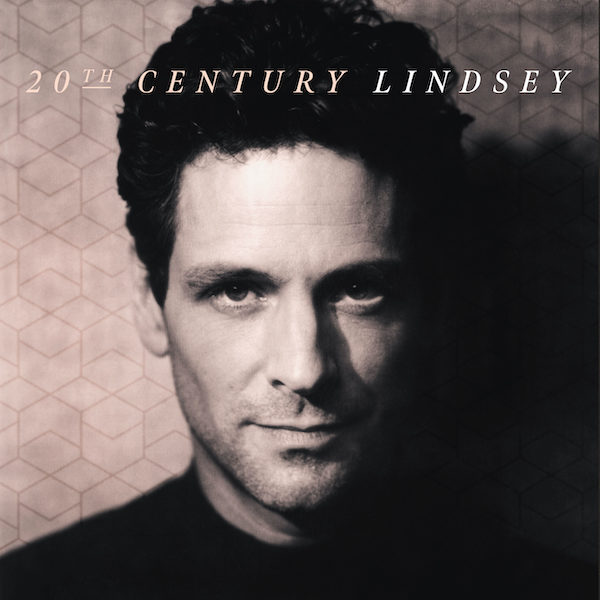

Lindsey Buckingham

20th Century Lindsey

Rhino Records

“Holiday Road” was the first standout Lindsey Buckingham song to come as a surprise for me. It not just became the aural billboard to the Vacation film series, but it was such an abstract standout to emerge from the weird and wonderful world of the 1980s. This was not your Fleetwood Mac Buckingham; this was an artist with free reign of creativity and a simple request from Hollywood’s greatest 1980s directors, Harold Ramis.

Looking back at the song, Buckingham sounds as comfortable about penning the emotion of the traditional family vacation as I am writing about the intricacies of his guitar work. It boils down to curiosity from a voyeur’s perspective. The feeling bleeds into the dystopian office culture of the 1980s. And with that, it breaks free from the nuclear family annual roadtrip and turns tradition upside down.

From being a guitarist to being a songwriter, Lindsey Buckingham was never an orthodox musician. 20th Century Lindsey collects his three solo albums and a fourth Rarities LP that pulls together his songs for films like Twister and the National Lampoon movies to extended cuts. This collection pulls together Buckingham’s creative mind into a beautiful box that highlights one of the 20th Century’s most unique rock musicians.

Describing Buckingham’s career is complicated. It’s like talking about the universe — beautiful, mysterious, quirky, magnificent. And to describe his life within the confines of his solo work, this modest piece cannot do it justice. But the albums together at face value can, and that is where the focus lies. Rhino is doing its due diligence to keep these important pieces alive through added remastering.

Thanks to the lackluster sales of Fleetwood Mac’s Tusk versus the success of Rumours, it gave Buckingham the fuel to go out on his own. And thanks to his solo work, it provided the initiative for Fleetwood Mac to expand their minds with Mirage and Tango in the Night.

And, thanks to punk and bands from The Clash to the Talking Heads, it gave him the courage to fully explore his potential, viewing songwriting as abstract paintings for little films. The first impression with 1981’s Law and Order feels like The Tokens but fits right into the concatenation of the times. Compared to the standout song, “Trouble,” it really sticks out, but it sets the tone for the future. But even here, he relies on Fleetwood Mac musician Mick Fleetwood to provide the drum tracks.

It feels like there are three personalities to Buckingham’s work. Law and Order was the quirky psychedelic pop reaction to ‘50s and ‘60s rock that is almost Zappa-esque (“It Was I”) or the bottom of the bottle diner ballad (“September Song”). What makes this album fun is its irony in the same way that David Lynch found irony in suburbia.

And irony is the genesis to Buckinham’s defining moment. But like every song Buckingham releases, it is a thoughtful progression to the next level. And that leads to Go Insane.

This album was Buckinham’s moment. It showed unique creativity and vulnerability, an album released just after the breakup of his former girlfriend, Carol Ann Harris. It also showed versatility, an accomplishment being that most instruments were performed by himself. What this led to became expression through intense passion (“Slow Dancing” and “Play in the Rain,” the second song demonstrating musique concrète in the form that was intended to be listened to — one part at the end of side A with the other part at the beginning of side B). Go Insane is Buckingham at his most fascinating. You want to understand how his mind works and dissect his vision. As simple as these songs seem, there is so much layering that goes on. What’s wild is that it came from a personal 24-track home recorder (that then was transferred to a 40-track system). But for him, the charm of being a musician is all about the process and this album is the process coming together to form a moment in time that funnels the idea of escapism guided through human nature. The album ends with a dedication to Dennis Wilson of The Beach Boys who died the December before the album was released, using an interpolation of “The Bonnie Banks of Loch Lomond” possibly for its positive sunny perspective in the folk songs lyrics.

Out of the Cradle was Buckingham’s “guitar” album. He is known for playing exclusively fingerstyle, although, if he wanted to create a clear sound, he reaches for a pick. But leading into the album with an “Instrumental Introduction” before “Don’t Look Down,” he shows off the versatility of his fingerstyle that brings out the guitar first instead of using guitar as a stylized component of the song. But that quickly changes when it all becomes part of the larger scope. Adding Richard Dashut, who had worked with Buckingham during the Fleetwood Mac days, helped to realize the big picture and give the album a polished depth with Phil Spector-like results. To create this effect, all of the instruments were recorded in mono while the guitars were plugged directly into the mixing board. Buckingham used nylon strings to make things sound lighter. As accessible as these songs feel, his intricacies stand out in such a wonderful and mystifying way. “Soul Drifter” is the perfect example. Gone is the creative process fueled by synthesized abstractions like Laurie Anderson and Gary Numan. Buckingham finally created an album that provided the sonic depth of Paul McCartney, Brian Wilson or David Bowie. Third time’s charm.

20th Essential Lindsey is a testament to rock and roll’s finest guitarist and stands in his musical immortality even if that moment only lasted just over a decade before he returned back to work with Fleetwood Mac. It all goes hand and hand and this is just a chapter in a much larger story. Buckinham’s dialectic represents a much larger lexicon of 1980s American society, more than we realized at the time.

And the more you understand Buckingham’s work, the more it opens your mind to a greater thought process — the sign of a brilliant composer.

No Comment! Be the first one.