With his new book Unusual Sounds, author David Hollander is the hero to the outreach and preservation of vintage library music

You may not remember when it was. And, you may not recall where you heard it. But, chances are, you have experienced a song or songs from music libraries. Science fiction, horror, ‘70s action films, cop funk, giallo, blacksploitation films, drive ins, these are all genres that are a consequence from the effects of library music. Unusual Sounds, The Hidden History of Library Music, traces the unexpected history through labels, composers and experiences of the time.

Unusual Sounds: The Hidden History of Library Music

Vintage music libraries have tapped into the collective conscious with their dimensional sounds and emotion-driven orchestrations glowing like a mood ring through time. From the Monday Night Football theme to the music from Night of the Living Dead to Keith Mansfield’s famous Prevues of Coming Attractions jingle “Funky Fanfare,”—an obsession of grindhouse and drive-in film junkies—these are examples of how library music has affected modern popular culture. And the monument that still reigns is the The People’s Court theme.

“The People’s Court Theme is an interesting example of library music because it also had a life in the UK as music for crime drama before it got discovered by The People’s Court,” said David Hollander, author of Unusual Sounds. “Then that usage becomes suddenly identifiable everywhere in the world. Strange enough, The People’s Court has reached the farthest corners of our earth. Those two records that it is from (Alan Tew’s “Drama Suite Part I and II”), they are really fantastic records because they contain all these little links and stings and bridges that are 6 to 10 second pieces of music. They are sublime and extensively used because they were friendly to the editor.”

Alan Tew – The Big One from Drama Suite Part I and II

Hollander is credited as a music supervisor for Adult Swim and the film Black Dynamite, which stemmed from his obsession with library music and later transformed him into an expert in the field.

He started as a collector, discovering the Thomas J. Valentino music library at a record store in Los Angeles. As a record collector, he was attracted to strange albums and eclectic soundtracks. When he saw the white sleeve cut out to expose the Valentino label, he was hooked.

“Everything about library music I like. I like the simplicity of the presentation. I like the utilitarian nature of the music. Ultimately it was geared toward film, and it was film music. I like this idea a composer was trying to make music for pictures that did not exist.”

That is the foundational philosophy to the incidental vibrancy of library music’s existence in the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. It was predominately a European market with composers like Brian Bennett, Nino Nardini, and Ennio Morricone being commissioned to make film music for films that did not exist yet. For filmmakers like George Romero, it was cheaper than hiring an orchestra to create music for a specific film. He says in the book’s introduction, “The composers of all this music had conjured the needs of low-budget filmmakers and provided scores that could be bought for a fraction of what it might cost to hire a composer and / or an orchestra.”

For Hollander, he began collecting at an expedient pace, trying to absorb as much library music as he could find, first collecting most of the CAM library. “I plunged headlong into it and started buying as much music as I could, eventually amassing thousands of library records. In many cases I was getting them from the libraries themselves and getting full runs. I did a couple of huge buys that I think would not be possible today. There were hundreds to a thousand records at a time.

“I remember one purchase where I bought through the mail. It was something like 900 records from this one guy. This was the ‘90s before the Internet and eBay, and he had me send him a money order. I thought this guy could totally rip me off. There was no checks and balances in place. Because there were so many records, he would ship me packs of fifteen to twenty at a time. There were all these packages that took about a year to send. I really did not know what was in the collection.”

Most record collectors would stop there. Not Hollander. Curious about these works and the current state of library music, Hollander found himself on a plane heading to Europe.

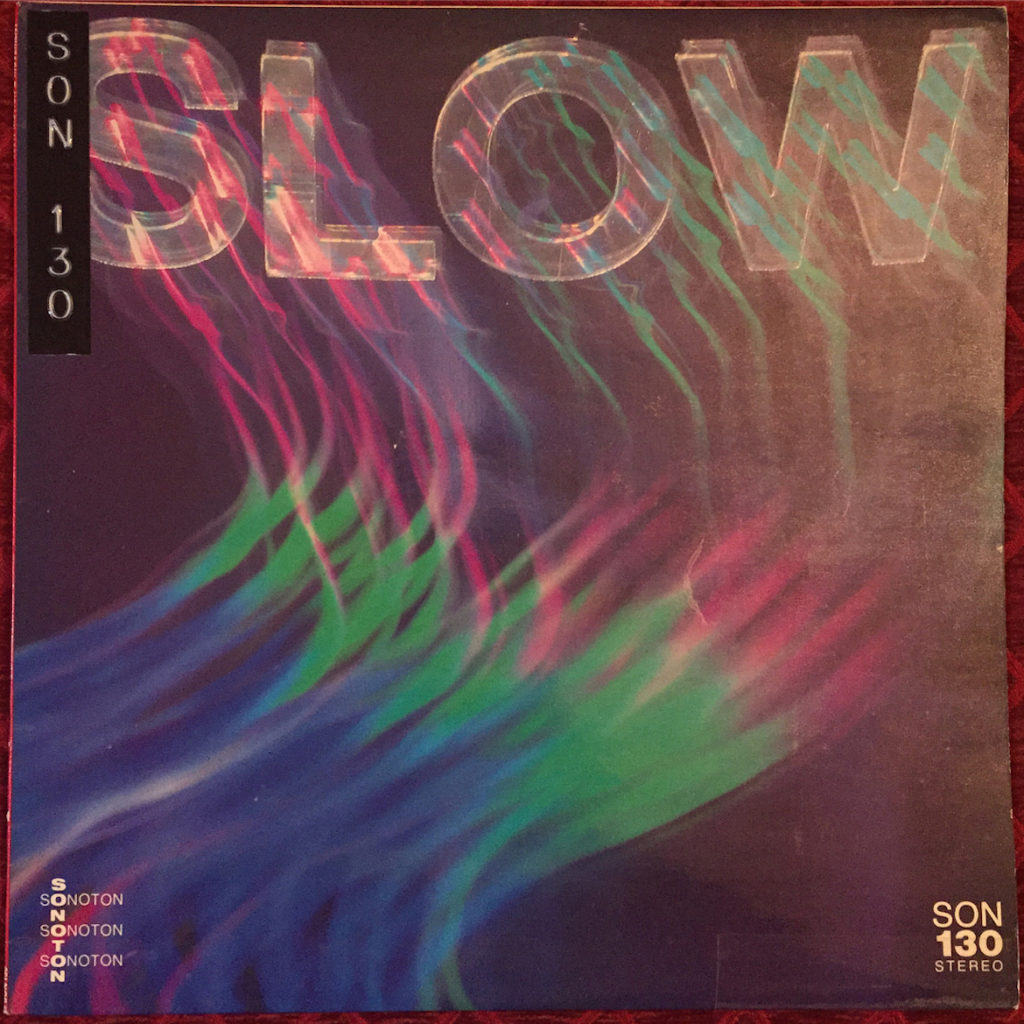

“I went to Europe and just sort of showed up at the offices EMI in Britain and Hamburg, Sonoton in Munich and some other places in the UK. I wanted to see the master tapes on the shelf, take pictures, and establish to what extent are they concerned with their archival assets and have the tapes been digitized? Were the tapes falling apart?

“What I found for the most part was not an effort to digitize this stuff. They were just collecting the performance. I would like to think that by virtue of my efforts and other people’s efforts at synchronizing and preserving and raising awareness of library music, the major labels began to seriously digitize.”

While there, the biggest challenge he faced was that label executives did not take him seriously. They thought he was an obsessive collector.

“There were two kinds of people on the hunt for library music and one were record collectors. They initially thought I was a superfan just out of my mind. I remember standing with Peter Cox at EMI 20 years ago, holding the master tapes to the Alan Tew ‘Drama Suite Part 1 and Part 2.’ I said do you understand I am holding the master tapes to one of the greatest pieces of British cop funk ever created? And they looked at me and said British cop funk? Are you insane? That was not a genre that they were familiar with. But in fact it is a genre! I stand by the fact those albums are the British crown jewels.

“After doing the music for Black Dynamite, they got it. They realized you can score entire movies and prove the viability of the music. I think that is now over and now everyone is getting in tune with the lasting legacy of this music.”

Black Dynamite (Official Movie Trailer)

When Hollander went back to Europe to work on the book, labels were in varying states of music preservation. Although bigger labels have greater resources, there are corporate hurdles to jump through. According to Hollander, much of the music has been absorbed by BMG, Universal or EMI. Therefore, the transference becomes its own problem and major corporate companies do not know what the music really is.

“I am in talks with Universal France about helping them. It will take a proposal and a group of people like a board and they have to approve funding. A lot of it has to do with the corporate side of preservation.”

For a composer-based library like Sonoton, they had control of all their masters and have thoroughly digitized the library themselves. “The smaller companies tend to use best practices implemented across the board. But with the larger companies, you never know. What it takes is visionary people in the corporate office, which can be a tall order.”

However, there are cases where libraries have been damaged or lost. In the book, Hollander talks about french label Southern / Peer, and how he missed rescuing the masters from the dumpster by about a week. Collections in labels sometimes are lost as owners change hands or the quality of tape is damaged beyond repair. There is a way to bake the tapes at a low temperature in order to keep the metal on the tape thus restoring them, but even that poses a risk. Luckily with current technology, Hollander says if you can find the LP, you can get a pretty good scan off it and many LPs are in very good condition because they simply were not played that much.

Albums and libraries often can be obscure and its historical lineage difficult to trace. One genre not extensively covered in the book is the Italian market, especially Giallo films.

“The thing about Italian library music, and I’m sorry I wasn’t able to cover more Italian library music in the book, what makes it difficult is the way they were structured. These labels were different than labels in other countries. It really was scores through mom and pop companies that would become music publishers. They create a library and because of it there has not been the same conglomeration like the British libraries, which is now controlled by just a few companies. That remains the situation with Italian library music to this day.

“One of the things I recognized when I was working as a music supervisor/music editor was that there was a real dirth of Italian library music available to use. And then of course there were cases of these high profile usage as in the case of “Curb Your Enthusiasm” which is Italian library music (originally “Frolic” by Luciano Michelini).There it’s really a successful use of the music. When I went to Italy, there is a reissue label from Rome named SONOR Music Editions, owned by Lorenzo Fabrizi.

“I saw that SONOR was talking to a lot of Italian composers and publishers getting master tapes. So we partnered with them and started a new music library called Intermezzi. We are just gathering and collecting vintage Italian music to then be used in film and television today. So it is fulfilling that mode for Italian library music out there. But I feel like I need to get my hand on more Italian library music because it’s this undiscovered country in a certain way.

“A lot of Italian libraries were only used in Italian films. So it never really left the country. The music of Giallo and the music of the crime thriller . . . the Poliziotteschi. All of that stuff is really well represented in Italian library. Now we are finding scores and scores of this music. In a lot of cases these are libraries I was aware of but not able to listen to in full. And I was able to do that with certain Italian libraries. One particular library we are now representing is the EdiPan library. It was a fairly big library curated by Bruno Nicolai. He made his own library and had a handful of titles. I did not get to look at the entire library. Usually I try to listened to entire label collections. So now I am getting to do that with Italian stuff, and it’s pretty exciting.”

Luciano Michelini – Frolic (from Curb Your Enthusiasm)

Not all songs from vintage library music are glistening masterpieces. Hollander admits there is library music that is sub par and nonsensical. “You do have to kind of wade through a lot of the material to get to the good stuff.”

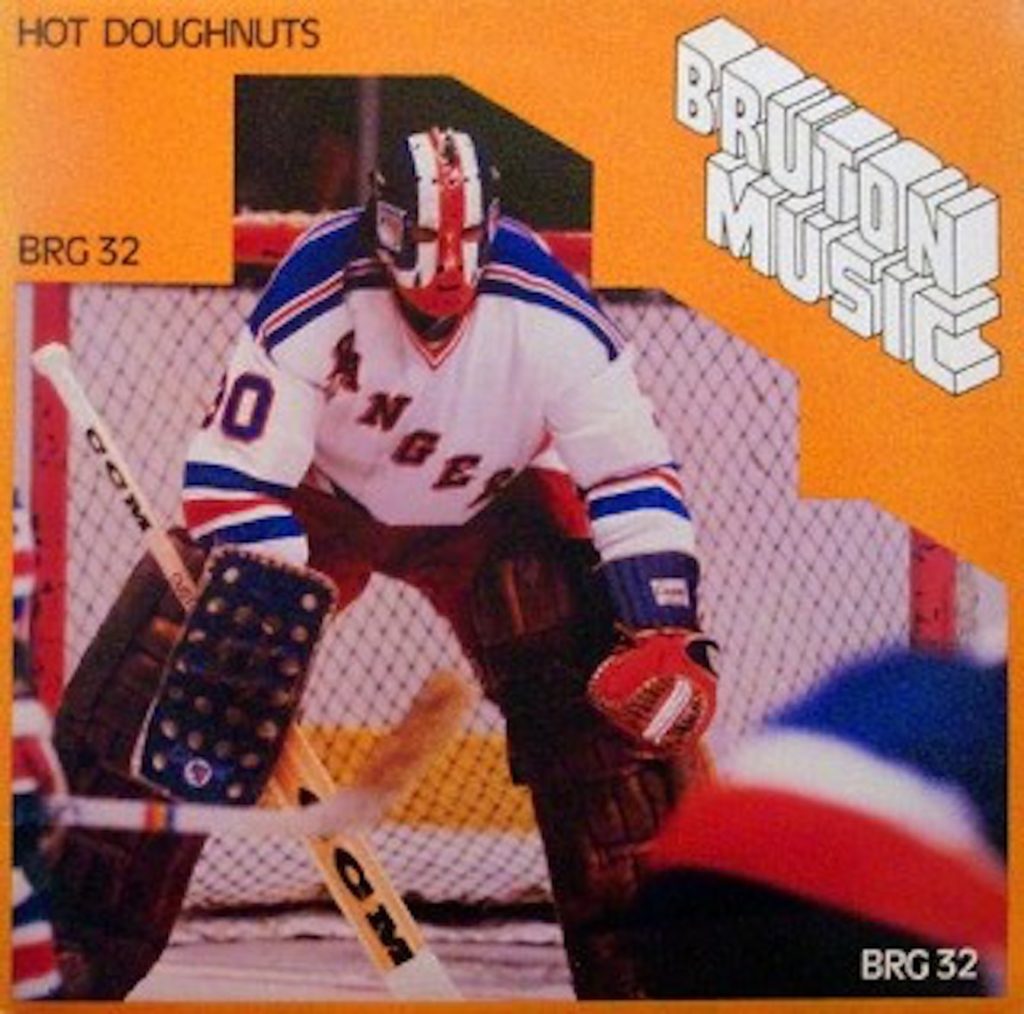

Yet, within the bad and the nonsensical like Music To Varnish Owls To or Bruton Music’s Hot Donuts, there are the diamonds.

“Sometimes you get a composer making library music who does not have the possibility of getting synchronized, but the music is interesting in its own right. One example I talk about is an Italian composer, Giampiero Boneschi. He has an album called The New Sound of A Voice and this record is out there. He was an older guy who did dance band music. Then he got a Minimoog and Model D and started making solo electronic records. The majority of them are described as abstracto and they are just that, really out there abstract electronic music. This guy was not coming from any of the places the other composers were. He became this countercultural freak. And A New Sound of A Voice is this weird electronic music with wordless vocals, like him scatting. It’s one of the best library records I have ever heard.”

Giampiero Boneschi – A New Sound of a Voice

Unusual Sounds is a grandiose achievement, not just documenting the importance of an eclectic music history through the labels and its composers, but also preserving the aesthetics of their album cover designs, thanks to artwork by Robert Beatty. Accompanying the book is the compilation release (on Anthology Recordings) that gathers the brightest stars of vintage library music together as a jumping-off point. The book is a culmination of many years of dedication and rigorous research. Labels now consider Hollander to be the foremost expert and archivist of library music. It’s not a bad title to have.

“The way it has worked out is that I have, by default, been the person these companies will come to. In certain cases I understand the chain of titles more than they do. They will come to me and say is this ours? We are now in this moment where there is an explosion of media. Tons of stations and channels and programming need music and there are more things being made than ever before. There is now a real need for library music and that will create an opportunity for vintage library music to continue to be important.”

![Film: The Apartment [1960] (Arrow Legacy) Film: The Apartment [1960] (Arrow Legacy)](https://www.selectivememorymag.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/6772_the-apartment-640-150x150.jpg)

No Comment! Be the first one.