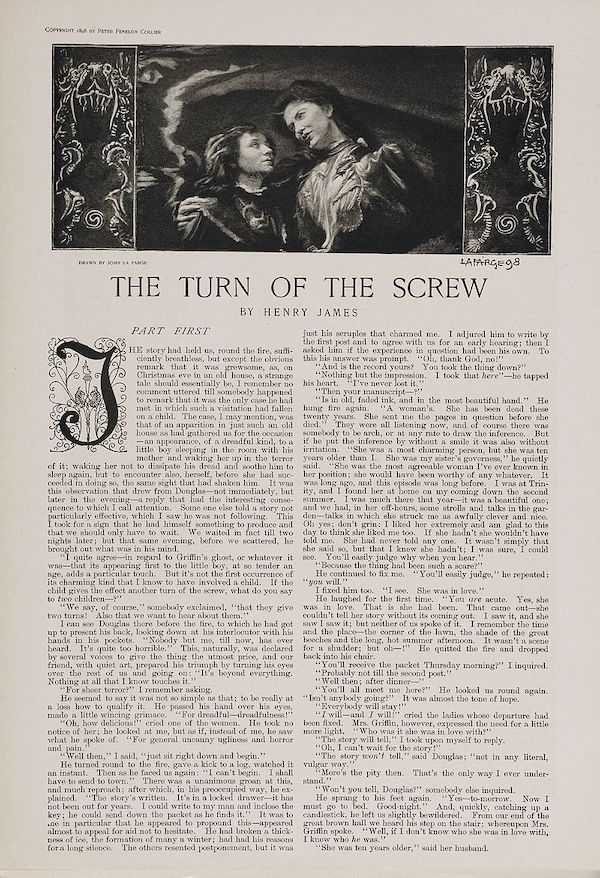

I’m a sucker for a good hair-raising ghost story and the 19th century was saturated with many supernatural yarns from the Victorian era as well as into the Guilded Age, especially with the invention of the photograph and moving picture. The ghost story was a sense of cultural commodity, embedded in its unearthly entertainment that preserved the oral tradition or mass produced through gothic literature—all thanks to the Industrial Revolution and the commercialized printing press. Before pop culture provided entertainment through new and exciting transmissions, families nestled in the darkness of night during long blustery winters and finessed the art of storytelling. Ghost stories were popularized at Christmas gatherings and accentuated through social rendezvous. A roaring fire to keep warm and voices flickering around the room, stories were a great way to get lost in the chill under moonlight.

Dr. Andrew Smith, author of The Ghost Story: 1840–1920, summed up the philosophical aesthetic of the 19th century ghost story:

“Throughout the 19th century,” says Smith, “there is a progressive internalization of horror, the idea that the monsters are not out there, but to be found within. That obviously culminates with Freud. With the ghost story there’s a sense that instead of being able to lock yourself away in your home, to leave the monster outside, the monster lives with you, and has a kind of intimacy.”

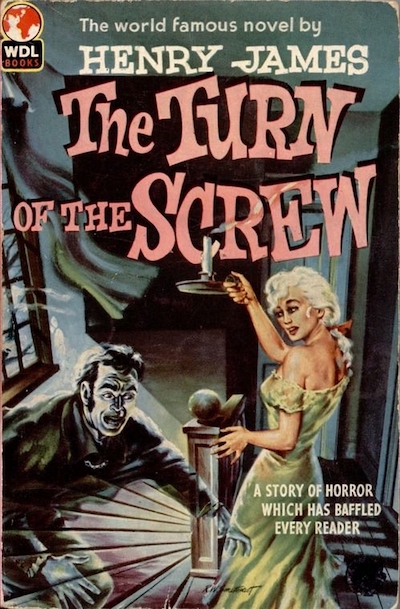

Smith’s observation best explains Henry James’s motive when penning The Turn of the Screw.

1898 experienced its fair share of ghost stories and horror hauntings through literature and folklore. Gothic literature peppered Western civilization with spine-chilling tales of the macabre. In 1898, tales of the supernatural spread across the country from The Capitol building to the “Blue Lady of Palmetto,” Hilton Head’s urban legend.

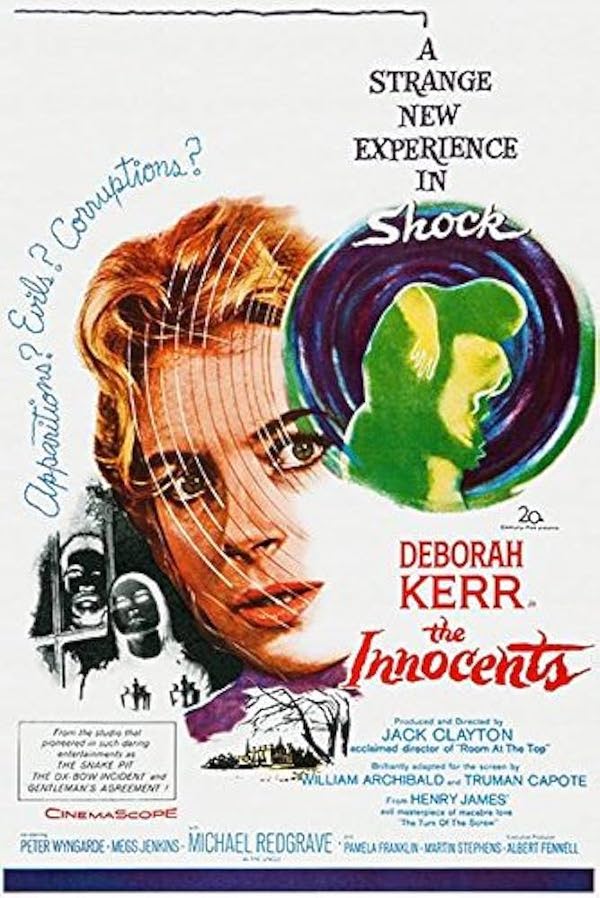

Henry James’s master ghost story is an immortal work that is still contemplated and discussed today. There have been many films and dramatic adaptations of the story—from films to plays to operas. The brilliant paranoia of The Innocents to the more recent The Turning and the miniseries, Haunting of Bly House. It now seems like the perfect time to dive in and read James’s original telling of ghosts, mystery and madness.

For a novella, the story provides depth. The chapters are very short but also dense in context and meaning. “The Turn of the Screw” is horror for the ghosts that inhabit the book, but it is more psychological for the mental corruption of the governess.

Building a background of the governess, she was the daughter of a country parson. At only 20, she has no worldly experience and through glimpses of home life, she is a nervous and emotional person. When she answers an advert in the paper, there is a sense of unannounced danger involved. The man behind the advert immediately safeguards himself by putting a wall up: The incumbent should assume all responsibility even to the point of cutting off all communication with him. There is a suggestion of a dim evil surrounding the entire situation.

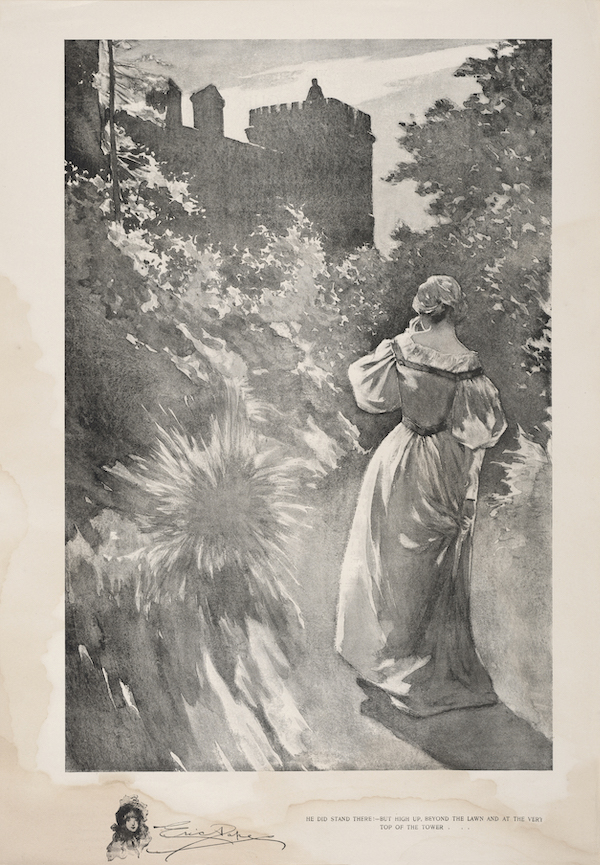

The governess begins to see the apparitions of two people, Jessel and Quint, who spent a lot of time with the two children of the manor, Flora and Miles. She begins to question reality and whether these sightings were real or pranks from the children. During this time, there is an infatuation of the governess that intensifies, and her duties are not enough. During an exchange with the housekeeper, Ms. Grose, she exposes a stereotype, “He seems to like us young and pretty. It was the way he liked everyone.” Is this penning the Master to be the villain of this story?

The deeper we get into the book, the more the fabric of reality is bent until tragedy happens and you are left to sit there questioning if it was real or if the governess experienced hallucinations through the manipulation of the children. This is brought on by insomnia where the governess falls into the trap of acting out the drama. Was that a ghost or a statue? Where the governess accused mischief of the afterlife, she then takes the shape of where she saw apparitions. Is this whole story an abuse of the imagination?

The book exploits the mode of the first-person narrative. We follow the governess as she journeys deeper into delusion until we are left to watch a murder take place. The novella has absolute power to frighten. James writes with unease. He frames the motives with an ending that is left to question what really happened. The ghosts in this story are merely props, a device to instigate action. The governess’s mental state is what changes this book into a psychological romp that involves the trick of the eye, possible illusion, and a massive architectural landscape with a house that becomes increasingly claustrophobic as the chapters progress. The governess finally blurs madness with reality and in that moment, death ends the book.

The governess just wants someone to love her. Her imagination creates the specter; a symbolism of dread as the rest of the tale unfolds.

Robert Weisbuch writes in “Henry James and the Idea of Evil,” “For fiction to be serious it had to be subtle. With Turn of the Screw, he renews the consequence of evil by problematizing reality.” As an American writer, he is free from the clutter of history Western civilization was bound by.

James left the conclusion of this book open ended. I’m not sure he could have easily wrapped a bow around this yarn and potentially continued to argue with himself for years after about what really haunted the governess. The story has been a part of decades of debate.

It’s the ending that turns a modest ghost story into something absolutely brilliant and terrifying. File it under a canopy of a historically creepy estate tucked in the countryside of England. The fright comes from the subtle details and pure storytelling at its finest.

No Comment! Be the first one.