I am always up for a good challenge. I find appreciation in someone who can take an idea, believe in it, and nurture it so that it blooms into its own identity and becomes part of the lexicon of thought. I say that within the caveat of reasoning and sound and authoritative research. If done properly, it not only allows the author to look at things in a different light, but it also makes the reader think differently about culture.

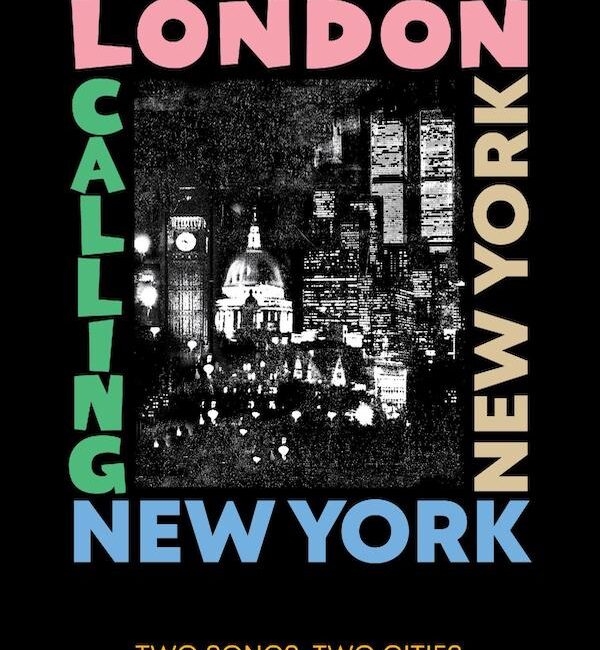

In London Calling New York New York, Two Songs, Two Cities (Trouser Press), the late British author, Peter Silverton, challenges us through a thoughtful look into two completely opposite songs, their societal impact, and not just what these songs mean in a cultural sense but also in a personal sense.

Silverton’s thought spins around forming an identity that lies in the power of place. Two songs that could not be more opposite and alike in its dimensional existence: Frank Sinatra’s “(Theme From) New York New York” and The Clash’s “London Calling.” Both songs were recorded in 1979. Both songs serve a specific purpose, and both songs could not be more important in forming a paradigm that is both historically timely and timeless at the same time.

Silverton builds credibility (not that he needs it) through shared experiences living in London, encounters with Joe Strummer and early performances of “London Calling.” He takes inspiration from Jon Savage and Greil Marcus and sets the stage through shared experiences.

That power is solidified from the very beginning and quotes he pulls from Nobel prize winner Derek Walcott where culture is identified by the cities we reside in. For Silverton, London was as much a part of him as he was it.

Identity is defined as “the fact of being who or what a person or thing is.” Both identity and mis-identity, Silverton defines its affinity through personal examples and struggles in health, culture, and the civic world we define ourselves in. Here is where we get lost in Silverton’s story, his genealogy, and how he intricately defines identity.

Realistically and symbolically, Silverton’s arrival to London was eclipsed by a fog, a moment he attributes to a “painfully true reflection of its own ills and evils in the industrialized perversion of the once innocent but long-ago poisoned early morning river basin mists that crept up from the Thames.”

This recollection alone is metaphorically the psychology of a socio-political landscape that was the gasoline to the punk genre. For Silverton, identity and place became the mental bonfire to deeply ponder the impact of “London Calling.”

Post-war scars fueled a political climate that exacerbated the welfare state and exposed that the hippy generation was not as successful as their intentions were, a second to its origins in the Beat generation.

By first exploring the origins of “London Calling,” we get a unique perspective into punk history and how a story is influenced by place (Cheyne Walk) through the lens of a cab ride, almost like a Hollywood tour. Here’s where Mick Jagger and Keith Richards lived. Here’s where Johnny Rotten had a flat. And here’s where Malcolm McLaren had his shop that ended up being known as World’s End, a name for the area dating back to the 17th Century.

Silverton paints a picture while illuminating perspective history and diligent research and a microscopic, detailed recount of studio recordings to tell a captivating story that feels fresh. To be a fly on the window listening in on conversations between Joe and his girlfriend, Gaby, in the back of a cab. Conversations that explored ideas like the Cold War and Three Mile Island. And all of that syphoned into environmentalism impact. Strummer’s lyrics for its time still hold true today that are symbolic, philosophical, and realistic. “London Calling” is a call to arms. It’s a list of action items slowly shaped in time and carefully crafted by the band. And though certain phrases stand out from the song, it’s the feeling of immediacy and anxiety that stands out the most.

What connects the two songs together the most is 1979. Silverton details the events that shaped the year through a broad hypothetical statement, “ . . . as dystopic and chaotic as 1979 was, it was also a year when the future began to arrive.” He treats the end of the 1970s much like those treated the end of the 20th Century and the Gilded Age. Two cities felt camaraderie in its brokenness. Picasso once said, “The purpose of art is washing the dust of daily life off our souls.” Sinatra did just that.

“If I can make it here, I can make it anywhere.” That line in “(Theme from) New York New York” is a pulse to the measurement of success. How New Yorkers defined success in 1979 versus today stood two different ideologies. At the time, it was considered survival. How we define success now is more subjective, but the lyric still reaches into the soul and replenishes confidence in humanity. This was Sinatra’s comeback moment. The song originates from Martin Scorcese’s film New York New York, a time capsule of 1940s Gotham.

The song was written by John Kander and Fred Ebb. The final product lives in a world of escapism that was written in Andy Warhol’s New York and the gritty underbelly that flooded the surface of urban life. Empty streets, a homicide rate out of control, neighborhoods that looked like a bombed-out third world country. A more appropriate comparison to “London Calling” is Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message.” But that was still a few years away.

New York City was a black canvas and through anger and optimism, Frank Sinatra was the one to grab a paint brush. Filmed and recorded in Los Angeles both song and film exhibit a city of dreams and a longing to fit in. In all of its power, Silverton does not shy away from the reality of the story, going into detail about the film and its conception, almost disastrous conclusion, and surprise failure only carried into prominence because of one song. In an instance, the song stands out by being a perfect reflection of the film itself. It’s the song that is today an identity to a city that uses it as a theme song once the New Year’s Eve ball on Times Square reaches Midnight and a catalyst for people of all ages to sing along adjacent to Taylor Swift’s “Welcome to New York.”

For both of these songs, there is no corner or crack that Silverton did not leave untouched, exhausting every angle for each song to compare and contrast. In doing so, we have a better understanding not just of the world at the time, but of our world at this time.

No Comment! Be the first one.